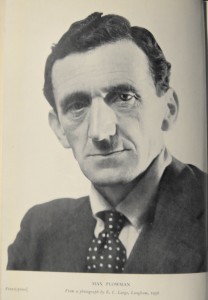

My great grandfather, Max Plowman was an interesting chap. I mean, you know someone is vaguely notable when they’ve been dead for over 70 years now and yet *still* has his own wikipedia page.

Max was born in London in 1883 and left school at 16 to work (for ten years) in his Father’s brick building business, somehow however, he managed to forge his way as journalist and poet.

From the very beginning of the first world war, Max felt opposed to it, morally, but on December 24th, 1914, he volunteered for enlistment in the Territorial Army 4th Field Ambulance.

He wasn’t particularly enthused, even days after signing up, writing to his brother, just days later:

I think the war is a bloody mess & how anybody can want to be mixed up in it beats me. No man properly alive ever kills another whether by machinery or bayonet so that war demands the grossest and foulest insensitiveness on the part of all who have to do with it – it’s an infernal soul-searching job and you’re damnably well out of it.

As explained by Jonathan Atkin in A War of Individuals: Bloomsbury Attitudes to the Great War, (pg 109):

Plowman felt that if he had ‘preached peace and internationalism’ in the period before the conflict this might have given him the moral authority to have declared himself a conscientious objector upon the outbreak of war. Now, however, he felt that he could not reject national responsibility in favour of that of a personal nature when he had taken previous advantage of the rewards of pre-war collective national responsibility (‘when the system of things one has prospered under has led inevitably to war’). Experience of war was to enable him to make a choice between public and personal demands. Plowman felt that if it was not for his experience of the military side of the inferno, he would have no right to profess his anti-war views and would have little sympathy with the ‘absolutist’ conscientious objectors.

He accepted a commission in an infantry regiment and served on the Western Front, at Albert, close to the Somme – his account of which can be read in his celebrated memoir, “A Subaltern on the Somme“.

In the trenches, Max received concussion from an exploding shell, and deemed to have shell shock, was sent home to recover, .

Whilst recovering, Max published a poetry collection and wrote The Right to Live – an anonymous pamphlet, an argument against the kind of society that made war inevitable.

Soon he wrote to his battalions adjutant:

For some time past it has been becoming increasingly apparent to me that for reasons of conscientious objection I wa unfitted to hold my commission in His Majesty’s army & I am now absolutely convinced that I have no alternative but to proffer my resignation. I have always held that (in the Prime Ministr’s words) was is a “relic of barbarism,” but my opinion has gradually deepened into a fixed conviction that organised warfare of any kind is always organised murder. So wholly do I believe in the doctrine of Incarnation (that God indeed lives in every human body) that I believe that killing men is always killing God.

As I hold this belief with conviction, you will, I think, see that is is impossible for me to continue to be a member of any organisation that has the killing of men for any part of its end, & I therefore beg that you will ask the Commanding Officer to forward this my resignation for acceptance with the least possible delay.

Max was not just opposed to the first world war, and unlike others conscientious objectors of the time, he did not wish different objectives to the war, Max was opposed to all war.

He was court-martialled and subsequently discharged from the army, swiftly becoming caught up in a bureaucratic mess as he now, as a discharged volunteer, he was liable for conscription. Applying to the conscription tribunal as a conscientious objector, he escaped conscription but ultimately was very lucky to avoid prison or worse penalties due to his stance.

Whilst without more investigation, I’m unsure of the exact details, as it is not something he is well known for, it would appear that Max was also friends (to some degree) with various figures in the early women’s rights/suffragette movement – in the 1918 General Election he assisted, Philip Snowdon (married to Ethel Snowden) in Blackburn in his (unsuccessful!) election campaign in Blackburn. Interestingly, Max also seems to have campaigned (unsuccessfully) in the 1919 by-election in Manchester Rusholme for Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence – a prominent early Womans Rights Activist. (It would appear he stayed about 15 minutes walk from where I live now, I’m guessing, based on pg 133, Bridge Into The Future).

(Apparently, my family still has a rocking cradle, given to us by the Pethick-Lawrences, which apparently I slept in as a baby!)

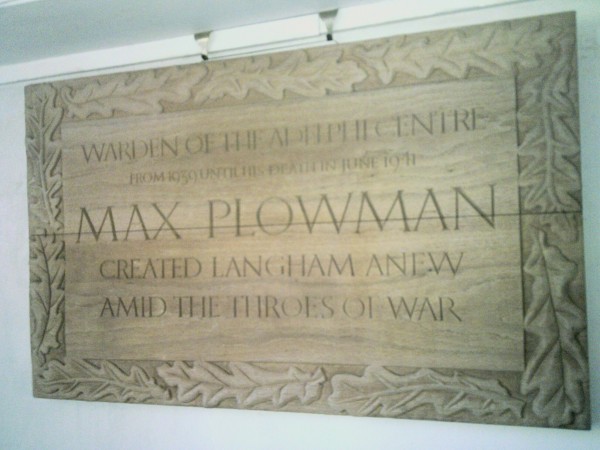

After the war, Max became even more involved in socialist and pacifist causes, and by 1930, Max had joined two other pacifist socialists in developing The Adelphi as a socialist monthly publication – which was closely aligned with the Independent Labour Party. Though the publication, George Orwell and Max became correspondents – with Max sending Orwell books to review, and Orwell contributing stories to The Adelphi.

In 1934, a canon of St. Paul’s Cathedral, sent a letter to the [Manchester!] Guardian inviting people to send him a postcard promising to “renounce war and never again to support another.” and over the following few weeks 30,000 pledged their support, resulting in the Peace Pledge Union. Max became active in the campaign, becoming the first General Secretary of the Peace Pledge Union from 1937-1938.

Max wrote a number of works throughout his life. He was something of an expert on Blake and Keat’s poetry, writing several books on the matter, though his war memoir, “A Subaltern on the Somme“, is probably the most easily accessible in modern times.

Max died of pneumonia, on the 3rd of June 1941 and is buried in the churchyard at Langham where he lived.